Staying safe on the water is the most important objective for any boat or ship operator. Yet there’s not enough clear, simple, and concise information on this very important topic.

I’m coming at this topic from the perspective of a fisherman in the Pacific Northwest, and more specifically the state of Washington. For many recreational boaters, bad or even marginal marine weather is simply a flat no-go. For us anglers, we are constantly attempting to walk the line between “safe enough to get some fishing in” and “*#&@ I wish I was back on the dock right about now”.

I own a 20′ Alumaweld boat with a 14-degree vee. My tolerance for difficult seas is almost zero. Yet, through that massive constraint, I’ve learned to really understand what makes for challenging or even dangerous conditions vs what allows me to get my fish for the day.

A lot of boat operators only factor in the weather and wind into their marine navigation plans, and this is one of the biggest and possibly life-threatening mistakes that can be made. Here’s an illustrative story on that topic.

Story time – Marine weather safety is about more than just the wind forecast

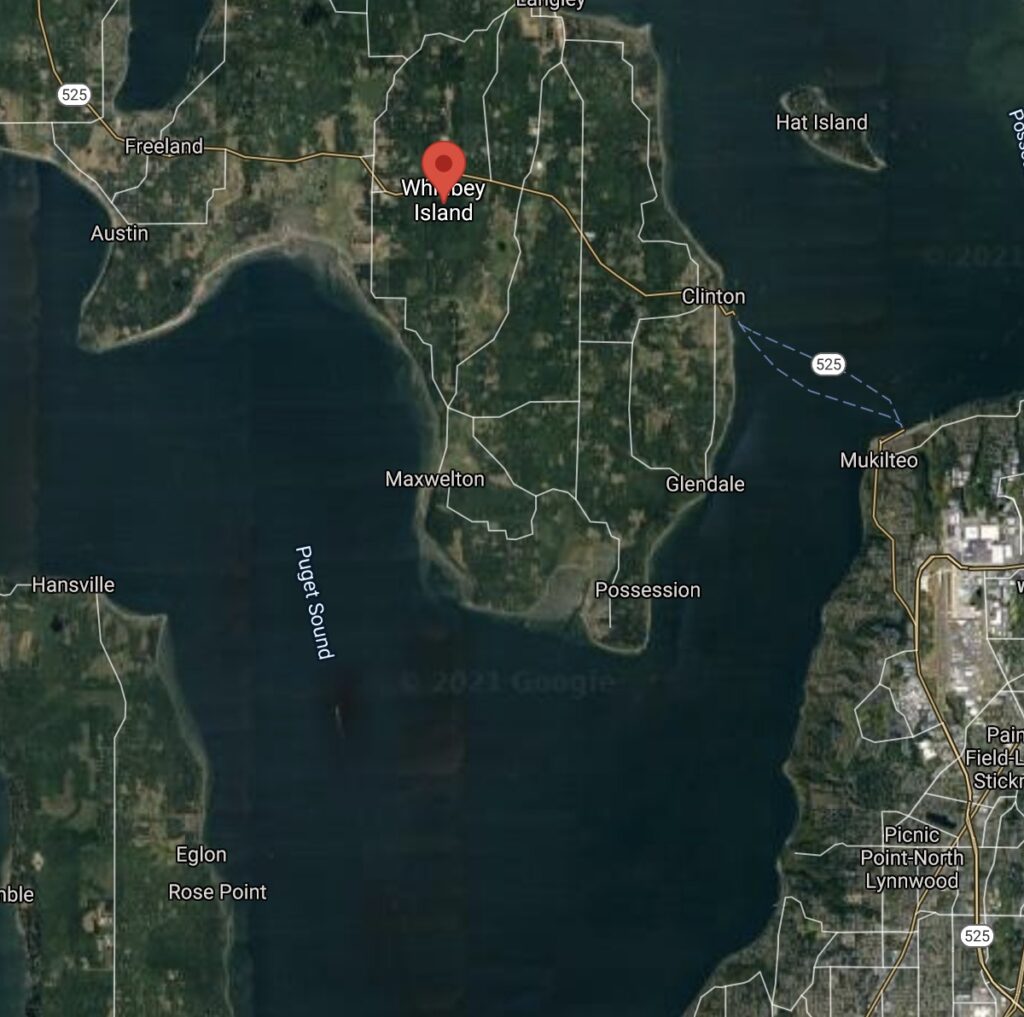

I wanted to take my Dad fishing for Ling cod during the season that typically opens from May 1st to mid-June. Halibut was also open on the day we were fishing, so we were kind of messing around near Point no Point. We wanted to run over to Possession Bar. There was a 12-15 mph wind coming from the south though.

If you know Whidbey Island and Possession Bar, there’s essentially maximum exposure to a south wind. We were watching massive bow waves with white caps breaking being generated from huge container ships navigating the area.

We decided to give it a go nonetheless and made our way onto the bar with an approach from the south.

We fished for a bit and hooked some nice fish, though none that we could keep, and decided to make our way back to port in Kingston after a full morning of fishing.

The wind had shifted to a slight SW angle, and I wanted to make the run back to Kingston with the shelter of the western shoreline of the Kitsap Peninsula vs fighting wind waves all the way back.

I decided to exit the bar in a mostly westward trajectory. As our depth went from 50 ft to about 200 ft, somewhere in there, we began to experience some of the biggest waves I’ve encountered in Puget Sound. In a short period of time, we were riding these waves and literally dropping off the top of them and then going back up the next wave.

My Dad fell out of his chair multiple times and looked at me with shock and surprise. In less than a minute we were through this awful stretch of water and back to the 1-2 ft wind waves we had been experiencing.

So what happened?

In this blog page we are going to cover a few topics related to marine weather safety:

- Understanding how wind speed, direction, and fetch effect marine safety.

- Understanding how tidal or river currents, ocean swells and wind combine to influence marine safety

- Understanding how underwater geography such as points and bars influence marine safety

- Discuss strategies in trip planning, safety equipment, and the all-important “Plan B’s” combined to always bring you safely to port.

For many boaters, following the old mariner rule of avoiding square seas is enough. As in, when swell height + wind wave height equals or exceeds the dominant wave period/duration, you stay on the docks. If you are confused, we will explain all of this later on in the article.

This rule works great if you have a proper offshore boat and you aren’t navigating around underwater geography that can create hazardous conditions.

Many fishermen though are trying to push that line between getting on the water to fish and staying safe. We only get so many days on the water to fish. Combine that with the scenario where people travel a great distance to a seaport on their all-important vacation/time off and really want to fish regardless of the conditions…

Nearly every year lives are lost at sea as a result of fishermen pushing the limit in marginal conditions.

At the same time, I’ve met people in big capable boats who are completely and needlessly terrified of big water. They will refuse to fish in the best water because they had that one bad experience and they don’t know what’s fishable and what’s not.

If that’s you, I’m not disrespecting you in any way, but I did write this article with you partially in mind, to attempt to break down the concepts and equip you with what you need to know to fish big water safely.

Disclaimer

I would love to share with you all my credentials that say you should listen to me, but the reality is, I’m just a dude on the internet. Now, I use my “non offshore” boat 50-60 times a year in the saltwater around Western Washington, so I have some experience, but more than anything I’m going to try to share what a lot of experienced people already know, but break it down into some easy to understand information.

When I was new to being on the water and I wanted to learn about how to safely cross river bars, and deal with marginal marine safety conditions, I found that there’s very little concise well explained material on the internet other than what you will find after hours of reading forum posts on fishing and boating. This blog aims to do a bit better than that and give you all of these concepts.

If you are reading this and you believe I’m in error on any of this, please comment or email me to correct it. I want to make sure boaters/anglers are equipped with the knowledge they need to stay safe and get out on the water as much as possible.

Understanding how wind speed, direction, and fetch impact marine safety

A few definition of terms:

Wind speed – Measured in Miles per Hour or Knots, usually an average not the maximum wind speed.

Wind Direction – The direction wind is originating from.

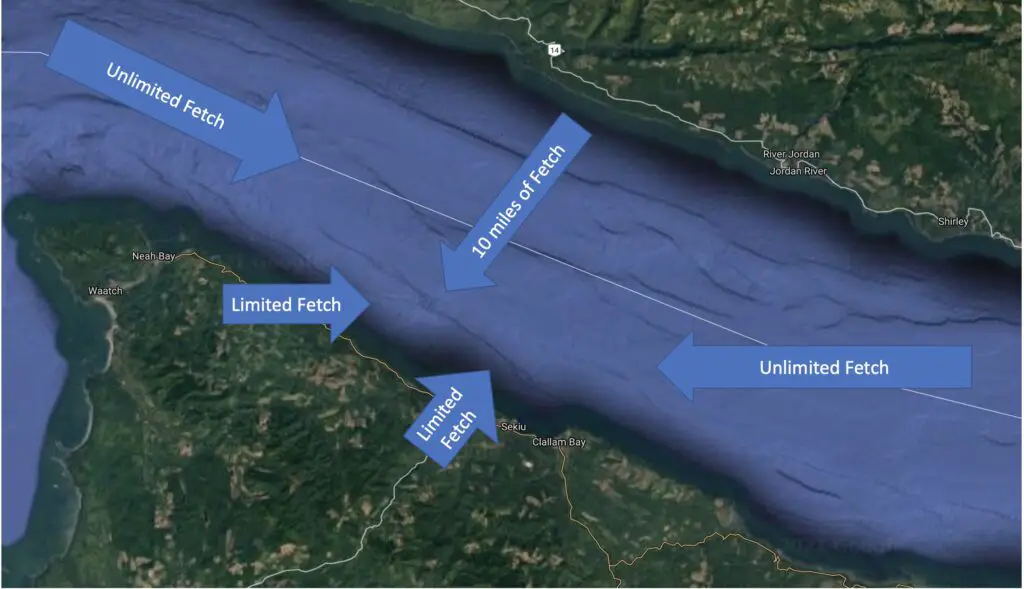

Fetch – The unobstructed distance that wind can travel over water in a constant direction.

It’s not possible to safely and reliably plan a boating or fishing trip on big water without knowing wind speed, direction, and fetch. Oftentimes, you can travel or fish in water that has nearby land which blocks the wind (creates minimal fetch). And there are other wind situations that are not as safe.

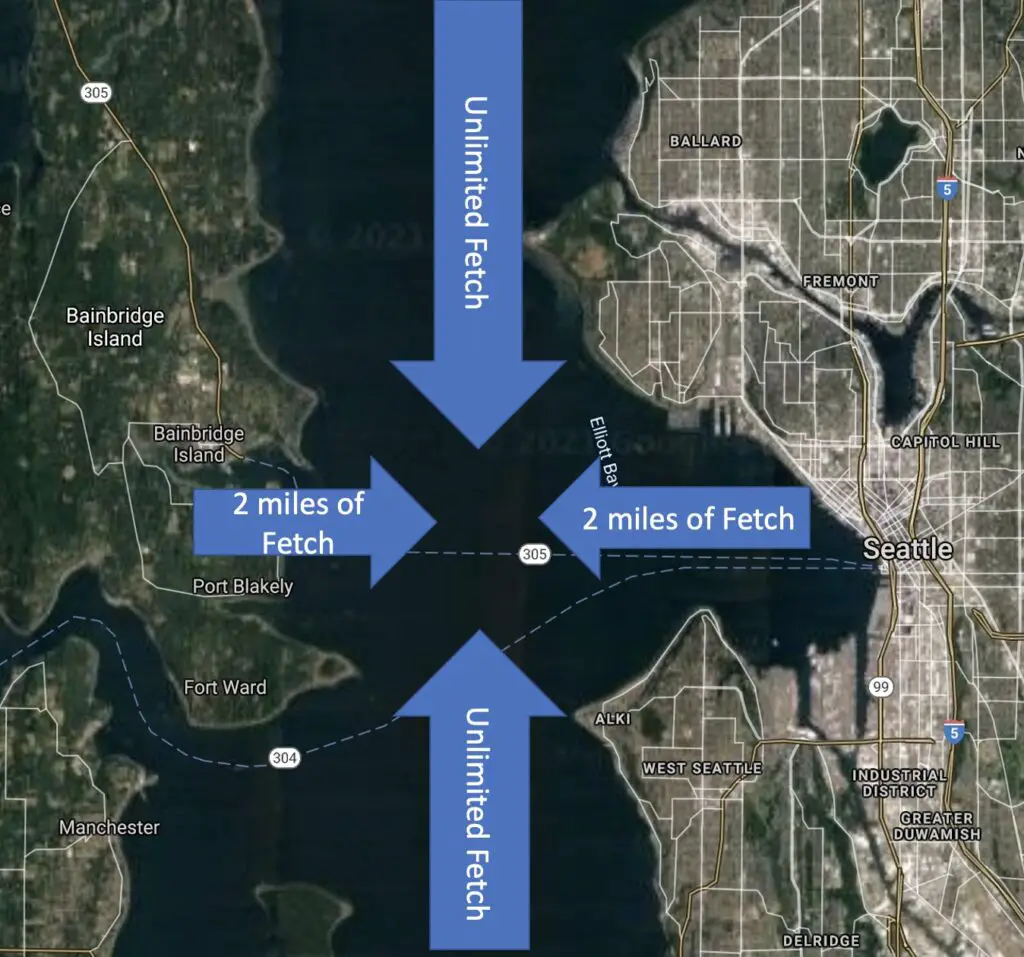

I fish a lot in the Puget Sound. The main interior of Puget Sound has land to the west and east and is only a few miles across. If you are fishing or boating in water around the City of Seattle, wind from the South or North has essentially many miles of fetch.

If that wind is say < 10 mph, it may not propose a problem. However, if the wind is 15-25 mph, this could create dangerous conditions for small boats. That same 15-25 mph wind may be tolerable if it’s coming from the west and you are hugging the western shoreline of Puget Sound.

Speed, direction, and fetch are all vital to understand.

Anyone who plans enough of these trips though knows it’s not just about getting to your destination or fishing spot. It’s also about getting back. Marine forecasts are quite uncertain and often unstable. I’ve seen many the social media post asking what people’s favorite wind prediction app is or complaining that the app they were using didn’t predict the bad conditions that showed up.

If your safe boating trip depends on the wind forecast being 100% accurate, you are putting yourself and your passengers in a potentially dangerous situation.

What if the wind is 5-10 mph faster than predicted?

What if the wind comes from the SE instead of the S?

What if the forecasted bad weather occurs at 12 pm instead of 2 pm?

Consider all of these “what if’s” before you get on the water and consider what your plan B is. Some examples:

- Leave 2-3 hours before bad weather is forecasted to show up

- Don’t run as far out as you were planning to go

- Look for sheltered water you can duck into based on wind direction / fetch if the weather turns

How does wind speed and fetch translate to wind wave size?

Remember that fetch is the unobstructed distance wind can act on the water. If a 15-20 mph wind has only .5 miles to act on the water it may generate 2 ft wind waves. If it has 5 miles of fetch it may generate 6 ft wind waves! This is a huge difference. One is navigable for many boats, and the other is quite hazardous for most recreational boats.

Understanding how tidal or river currents, ocean swells and wind combine to influence marine safety

This topic of waves and currents might be one of the most important related to marine conditions. It’s often misunderstood as well.

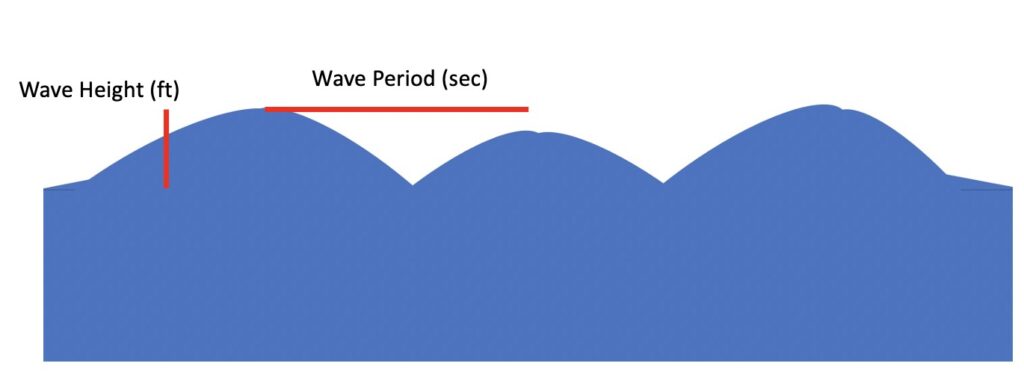

Swell Height – The height of “waves” that are generated far offshore but will still exist in areas without any wind

Swell Direction – The direction these waves are originating from

Dominant Wave Period or Duration – The time in seconds between each swell

Flood Current – Tidal currents caused by an approaching high tide sending water towards shore

Ebb Current – Tidal currents caused by an approaching low tide sending water away from shore

If you’ve ever noticed seemingly calm water turn into “sporty conditions” without the wind changing in speed or direction, you’ve likely encountered this effect of combining wind, tidal currents, and swell.

Which direction do most swells come from? If you’re on the Pacific side, it’s from the west right? Sometimes it’s the SW or NW, but always from the west. Swell is the leftover or residual “wind waves” from weather events going on way offshore.

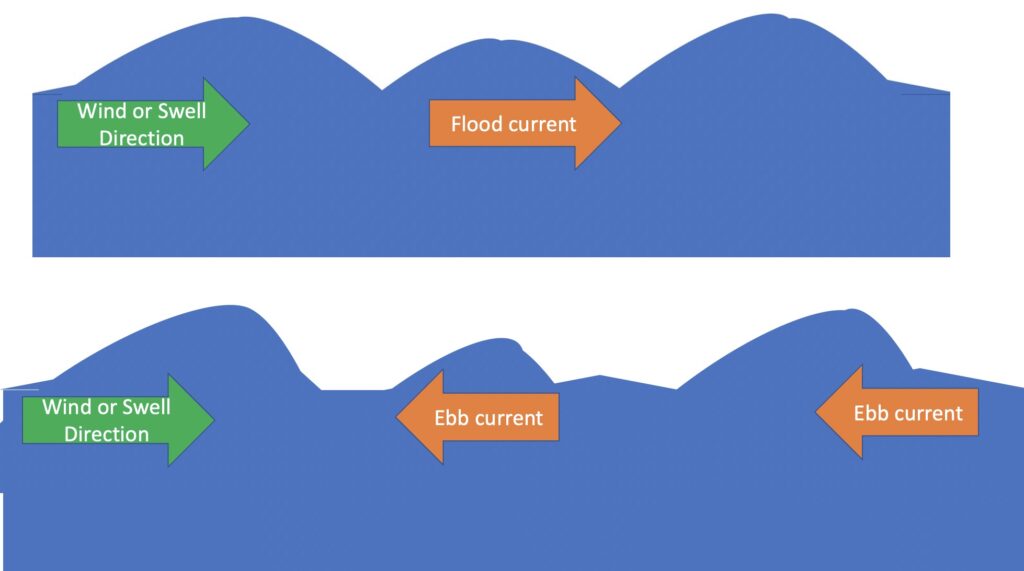

Which way does a flood current go? Well…in the simplest situations, flood tides always go inland, towards the shore, right? This does get more complicated in interior bodies of saltwater like the Puget Sound.

Now which way does an ebb current go? Away from shore, right?

Now, what we’ve just uncovered…and you may have to think about it, and look at these pictures a bit longer, is that an ebb tide is usually going the opposite direction of the swells. And a flood current is going with the swells.

This matters. Big time. Especially if you are traveling with the current that is traveling against the wind/swell direction.

Even with no wind…if you have big swells and a big opposing ebb current, dangerous conditions could exist for boaters and in particular over the wrong underwater geography (more on that next section)

Now, consider the following situation:

We have 6 ft swells every 10 seconds out in the Pacific Ocean. 5-10 mph winds from the S, increasing to 10-20 from the east. Depending on your boat this may be navigable…but what’s missing?

We don’t know anything about the underwater geography of the water or land we are traversing in and around.

We also don’t know what the tidal currents are doing! 6 ft swells every 10 seconds with light winds and a flood current is lumpy, but navigable water for a lot of boaters (not every boat!)

Switch that to an ebb current going from east to west and it could get really challenging. Add an east wind to 20mph on top of the ebb current opposing those swells and we are talking some nasty water!

Consider another scenario:

We are going over a river bar to head out into the ocean. The conditions are West swells of 5 ft every 8 seconds and 5-15 mph winds from the west. Looks potentially doable right?

Well…maybe…if that forecast is at 15 mph from the W instead of 5 and the time when we are crossing or returning over the river bar is during max ebb…watch out! Also, we didn’t share the flow rate of the river. Some rivers have periods such as after a recent storm when they are putting massive amounts of water into the ocean.

All that current from an ebb tide, river flow against a west wind, and west swell along the geography of a river bar can create dangerous conditions. Contrast this same forecast with a flood current, light river flows, and lighter winds and you have a very different scenario.

I’m hoping you are starting to see the importance of many details in figuring out how to safely plan a trip on big water and especially big water near shore scenarios.

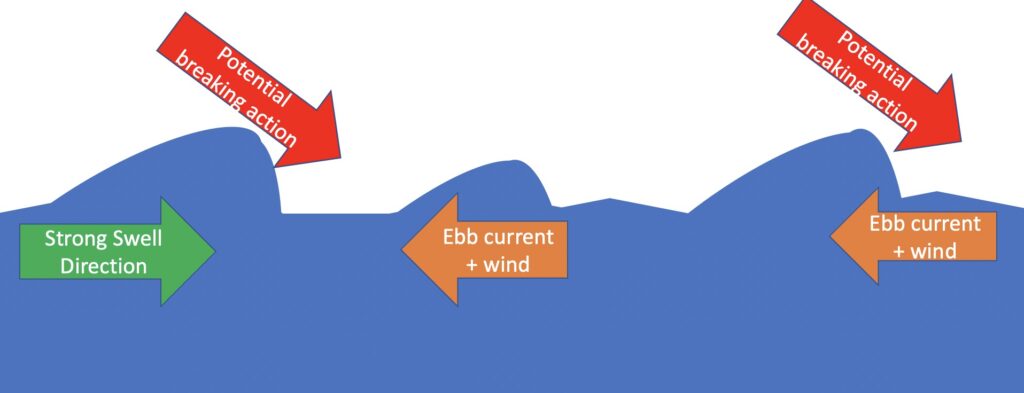

The key concept I want you to come away with is an appreciation and understanding of the physics of waves when there is an opposing force coming from a direction other than the direction of the wave (could be wind or swell generated). The opposing force could be wind or current (or both).

In the worst conditions, this dynamic of an opposing force (current or wind) against waves could lead to the wave being even more unstable and even breaking. Breaking waves are bad news for anyone in a boat attempting to navigate through them. Don’t mess with this condition and know via prior research whether there is a risk.

Understanding how underwater geography influences marine safety

I finally want to explain the story of my Dad and I fishing Possession Bar for bottom fish.

First some definition of terms:

Bar – A shallow formation of usually sand, often at the mouths of rivers and creeks.

Point – A portion of land that juts further into the water than the nearby coastline, usually extending underwater creating a shallower rocky area adjacent to deeper water.

Tide Rips – A stretch of turbulent water caused by one current flowing into or across another current.

Tidal Rapid – a fast-moving tidal current passes through a constriction, resulting in the formation of waves, eddies, and hazardous conditions.

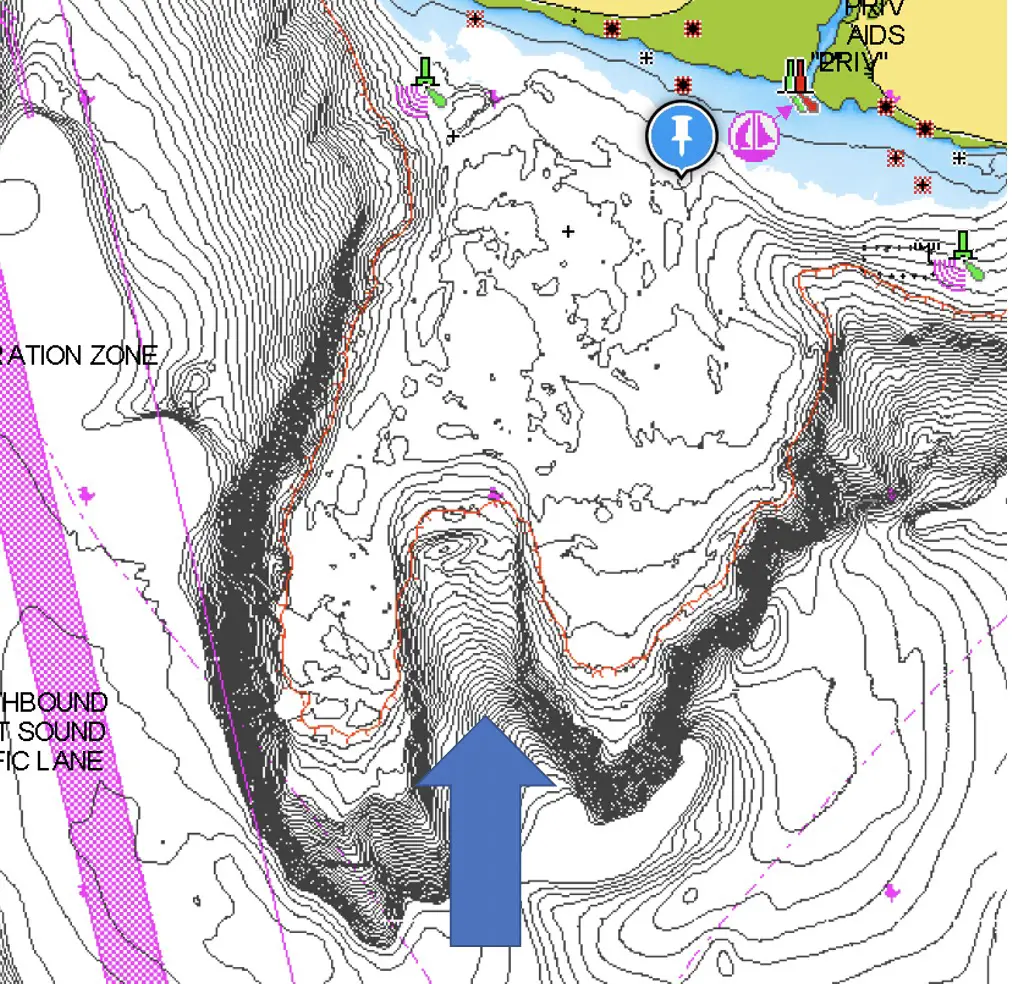

Another extremely important concept one must understand is that of how underwater geography influences marine conditions. When large volumes of water are forced through constrictions, either due to a sudden rise in the sea floor or due to land masses creating a pinch point the surface of that water often forms waves as a result.

River Bars and Points are two such types of constrictions where the sea floor rises suddenly. Anytime you are navigating big water closer to shore you may encounter river bars and point.

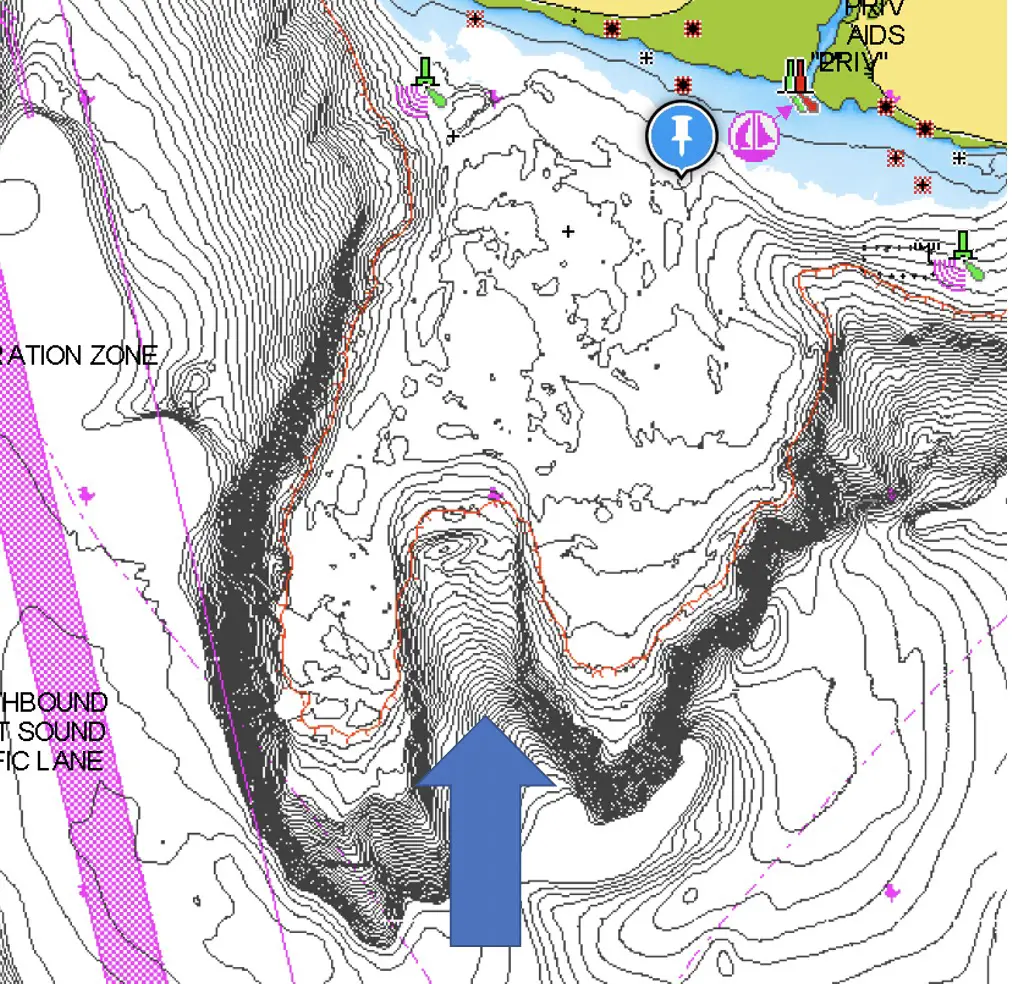

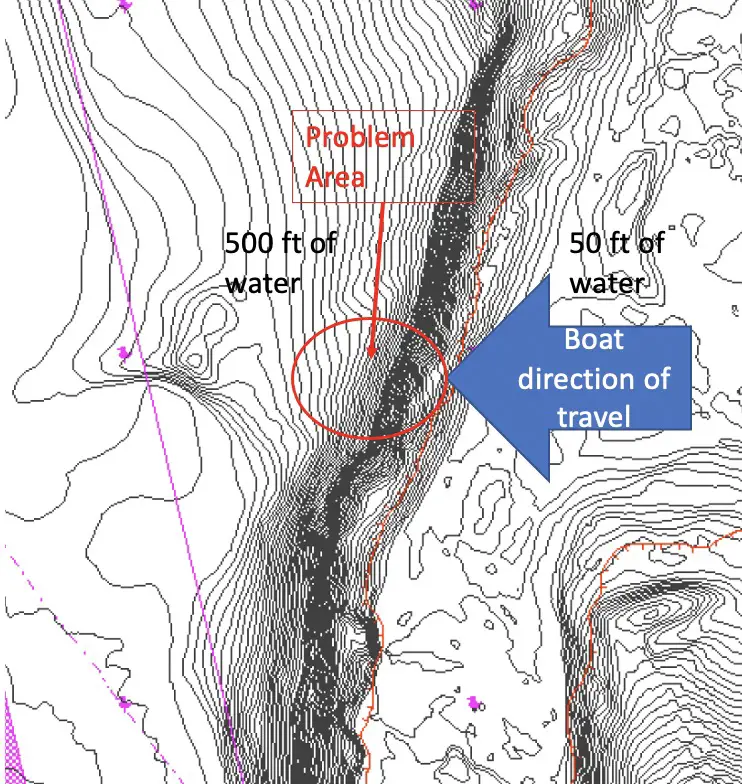

My Dad and I had made our way onto Possession bar from the south where there was a very gradual shallowing from the 500 ft depth of Puget Sound to the 50 ft depth of the bar. When we left the bar we exited to the west which meant we went from that 50 ft shallows to deep water very quickly.

What’s crazy is that we never even saw the 6-7 ft tidal rapid until we were in it. This is often the nature of these conditions. They cannot be accurately assessed from a safe distance. All of a sudden we were free falling off the top of these waves and staring at the next wave within a few seconds. The entire experience lasted less than 60 seconds and we were through and over the deep water of Puget Sound again.

The next time you think shallow water is where safety lies. Think again! In adverse conditions, the transition point where deep water becomes shallow or shallow becomes deep is often the most dangerous place to be.

This concept of underwater geography creating hazards can and often needs to be combined with understanding the wind speed, direction and fetch and the impact of opposing swell, wind and tidal currents.

River bars are classic places where all 3 concepts must be understood and come together to create marine safety hazards.

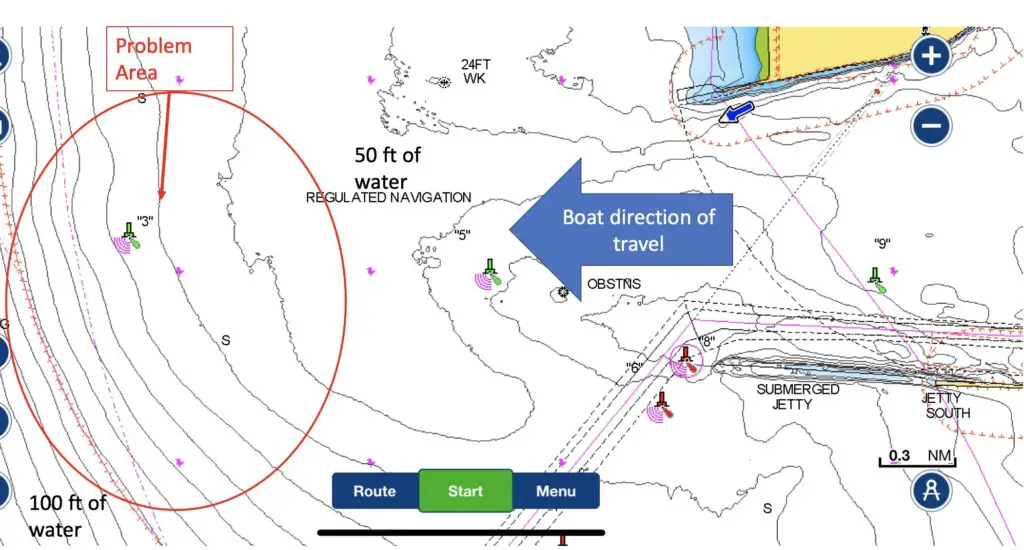

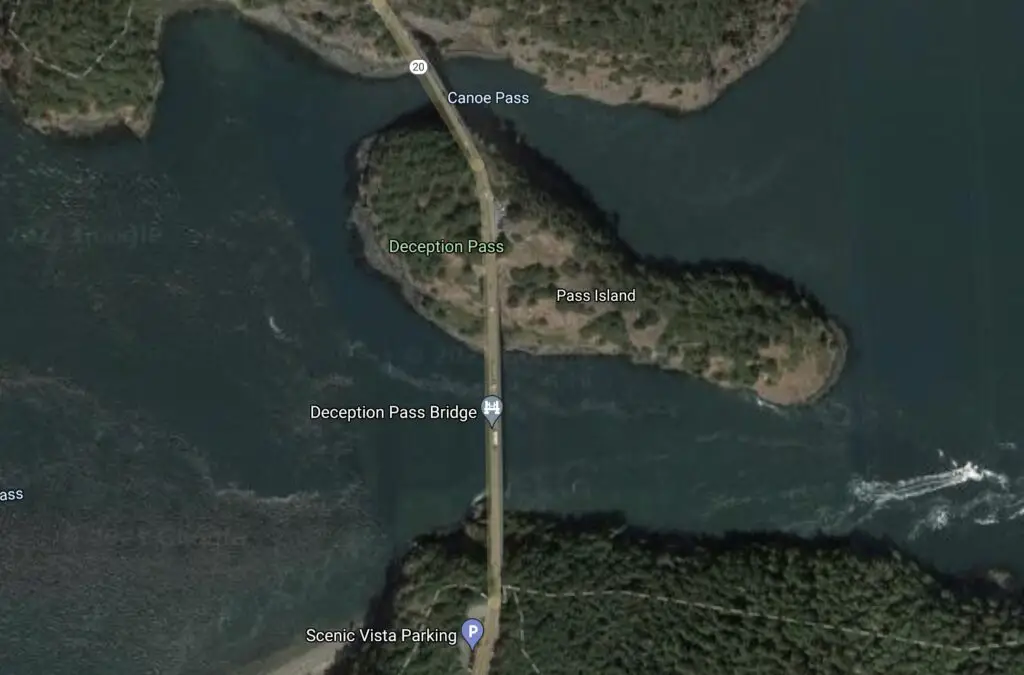

Another place that can present safety hazards are where land creates a pinch point.

Typically these areas will be between land masses such as a nearshore island, or could be a named “pass”.

Passes with particularly large bodies of water on both sides of the pass subject to tidal currents are areas to be very mindful of.

Absolutely massive tidal rapids can be generated when you have large swell or wind waves coming into one side of the pass combined with strong ebb flow as water attempts to rush out of the other side of the pass.

As recently as 2019 a boater lost their life when their boat capsized west of Deception Pass in some nasty marine conditions with 6-8 ft wind waves. Marine weather safety is serious business.

Strategies in trip planning, safety equipment and the all important “Plan B’s” combine to always bring you safely to port.

It’s great that some boaters are experts at navigating dangerous and rough water conditions. But you know what’s better? Planning to avoid all such dangerous conditions.

Now, you should know some of the strategies for navigating rough water, because even with great planning you may get caught. Or you may have planned with a slight risk of getting caught in bad conditions that turns into the real deal.

The reality is that most adverse conditions can be avoided through proper research and planning.

Here are some of the tools you will want to use:

My list of things I make sure I know before heading out

Know the Marine Forecast from NOAA. Here is the NOAA marine forecast for Washington State.

Compare the marine forecast to any available buoy data that show actual conditions, especially for river bars. I look at the National Data Buoy Center (part of NOAA) when I want this.

Know the high tide and low tide of the port you are leaving and returning to. I use saltwatertides.com to show me these tides.

Know the max ebb period for any river bars being traversed and plan to avoid this period unless conditions are very calm and ebb currents are light. I use the Navionics app for this.

Know the currents in all the areas you are traveling to / from. Consider avoiding constriction points during max ebb periods. I use the Navionics app for this.

Know the weather prediction for the day including hourly wind forecast, assume it could be wrong by 5-10 mph+, by exact direction and that bad weather could arrive 1-2 hours early. I use the Windy app for this.

Know the above water and underwater geography, pay particular attention to any bars, points or constricting land masses (pinch points) you will traveling or fishing around. I use the Navionics app for this.

Safety equipment is a must have on your boat

You are required to carry at minimum several pieces of safety equipment such as lifejackets and throwable floatation. I’m not going to list everything here as regulations change and I don’t want to try and keep this up to date. If you are getting your safety equipment ideas ONLY from this blog vs the US Coast Guard, you are already in trouble. Here’s a link to the boaters guide of federal requirements for recreational boats.

I will advocate for a few things here though. There are several Amazon links to buy marine safety gear on this page. As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases you make via the below links. Using the links below costs you nothing additional, but supports us continuing to put out quality content that hopefully helps you to enjoy the outdoors in the Pacific Northwest.

Consider buying the auto-inflate lifejackets you wear all of the time. The reality is you cannot always predict the moment you will need to scramble and put a life jacket on. These auto-inflate lifejackets are so comfortable you barely even realize you’re wearing them.

You should have a marine radio that is programmed for the USCG channel.

I use this handheld for my small boat and I make sure it’s charged prior to trips. I need to make sure I remember to leave it on when I’m far from port as even if I’m not in trouble, I may be the closest boat to someone who is.

Keep in mind that some handheld radios will need to be programmed for the standard channels that would come pre-configured on a “marine radio”. There are lots of good resources for how to do that on the internet.

Check the expiration date on your flares…I need to do that myself next time I take my boat out of storage!

If you are going to fish offshore you should really have a PLB like the below:

What’s your plan B?

Always always always have a Plan B. And seriously, if you have a bad feeling about something like the changing conditions or a stretch of water you don’t feel good about, just make the call and head in.

You can always accumulate experience and confidence over time if you make it back to port each trip!

No fish is worth a fisherman’s life. Period.

If you are going offshore, do you have multiple motors capable of getting you back in, in case one gives up the magic smoke?

Do you have multiple batteries fully charged and ready to go in case one of them fails? Something I do when I’m in an area where losing power would be a disaster, is I don’t turn off one motor until I’ve started the other one.

Do you have an anchor that can be deployed in a pinch, in case you lose power?

Do you have a marine radio?

Do you know where the sheltered water is in case you need to duck out of bad weather?

Do you know of the areas you should avoid if the weather turns?

Do you know which port you will go to if you consider it unsafe to go back to where you launched from?

There are many other ways to think about Plan B’s and as I get more feedback and thoughts around this I will update and compile them here.

Some of the best trip strategies for marginal weather

Here’s one of my favorite strategies when weather conditions are marginal and I’m trying to decide on a go / no-go situation:

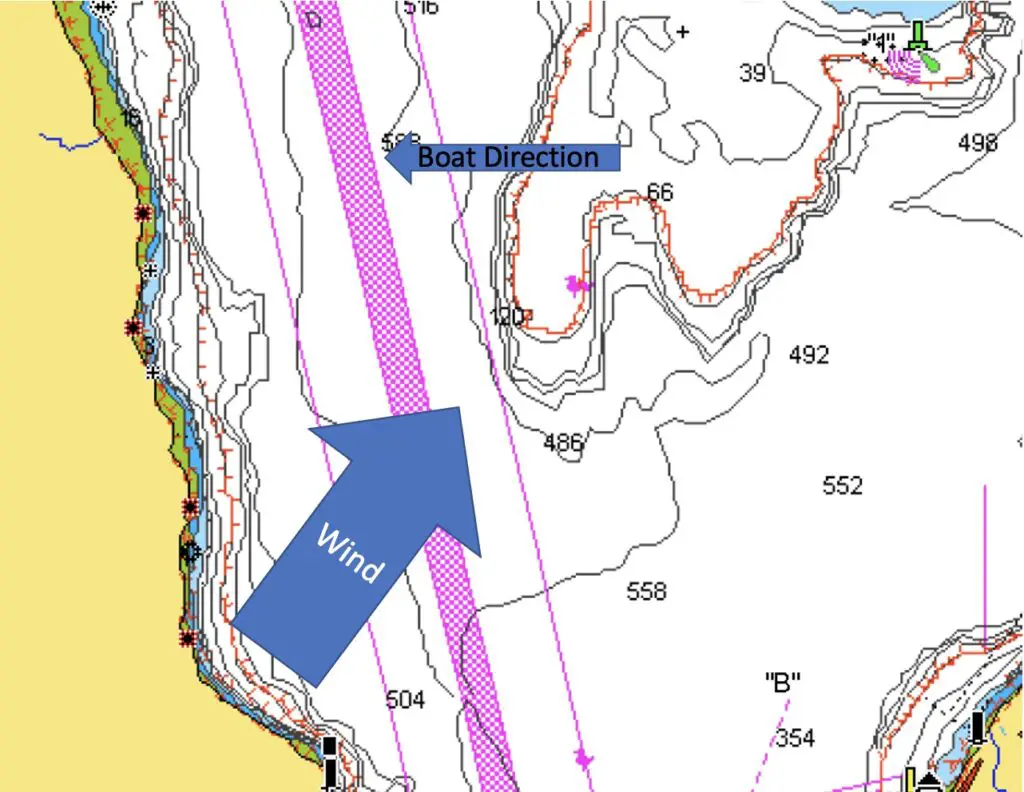

Travel with the wind back to port.

Wind waves are steeper and create more impact on your boat when you travel into the wind vs with the wind. If you are in a smaller boat or one like mine with a shallower vee hull design vs an offshore boat that can cut through wind waves, you may not be able to stay on plane going into the wind vs going with the wind.

If I’m doing trip planning in marginal weather, and I can get out there to the fishing grounds safely and have the wind at my back on the return, often times I will go (unless the wind is really bad).

The situation you want to avoid is one where you have the wind at your back traveling to the fishing grounds, and you get there on plane, but now you are getting beat up and crawling along trying to get back to port, while the weather is worsening…this can be a disaster. Simply don’t go in that scenario.

Navigating following seas and other hazardous water

When you are traveling the wind at your back, you need to mindful of one of the most dangerous marine conditions to navigate, that being “following seas”.

Following seas are when the dominant wave direction is at your boats stern. If these waves are small, its not a big deal, but when they are larger (depending on your boat), it’s strongly advised to travel at the speed of the waves vs going over the top of the wave.

Keeping the bow pointed up and staying on the backside of a wave vs slowing down and getting caught in the trough, or speeding up and potentially plunging at too steep of an angle into the next wave. Prayerfully, we won’t ever find ourselves in this kind of water, but it’s important to understand how to navigate and to make sure you don’t panic.

I’ve read too many boating disaster accounts that involve boater panic, trying to get out of bad weather and going too fast with large following seas. One of the pieces of sage advice I’ve heard here is “Your boat will handle about 2x worse water than you can”. You don’t need a huge boat to survive nasty weather (though it would be nice!), you just need to stay calm and patient to give you and your crew the best chance.

Other advice from the US Coast Guard for navigating bad weather:

- Reduce speed to the minimum that allows continued headway

- Make sure everyone on board is wearing their life jacket

- Turn on navigation / running lights

- If possible, head for nearest safe-to-approach shore (consider the above about inshore dangerous water!)

- Head boat into waves at a 45-degree angle

- Keep bilges free of water. (I will run my bilge continuously at times)

- Seat passengers on the bottom of the boat, near the centerline

- If the engine fails, deploy a sea anchor (or bucket if there’s no sea anchor aboard) from the bow

- Anchor the boat if necessary. (Know how to do this safely depending on the water conditions!)

Wrapping up the marine safety topic

Because I use my boat so much during the year I’ve rapidly accumulated significant experience, but I’m still a relative newbie on a lot of this. If you’ve read this and you think I’ve left something off that’s vital for fisherman / boater marine safety, please drop me a comment or email me (kyle@pnwbestlife.com) and I will make the correction / addition as appropriate.